"Waiting

for the Axman"-

The

Axeman Panic of 1912 in Texas

By Charles Swenson

(Photo courtesy of Fayette Public Library and Archives)

On a bright spring day in April of 1912, a local delivery man

named Ed Deere came into the newspaper offices of the Bryan Daily

Eagle and Pilot to talk about the latest news that had been rattling

black communities throughout Texas and Louisiana. Just fifty miles

away in Hempstead, Ike Burney and his daughter Alice had been

brutally axed to death. The murderer had been frightened off by

another daughter who had rolled under her bed after she was

assaulted, escaping the slaughter when her screams frightened off the

killer. They were the last victims of the Axman, one of the names

given to arguably the most prolific serial killings in American

history, involving at least forty five men, women and children in

twelve families in Louisiana and Texas. These horrendous crimes remain not only unsolved but virtually unknown over a century later.

The Axman murders created a tremendous wave of panic among black

communities in Texas and Louisiana between 1911 and 1912, a

widespread fear that one's entire family might be wiped out in a

horrendously brutal fashion while one slept at night. This terror

was well justified and a very real existential threat to blacks in

Louisiana and Texas in the spring of 1912. The ensuing panic was

surprisingly well documented by the press at the time due to the

sensational nature of the murders and lurid tales of voodoo swirling

around them. Another name given these killings hints at why these

murders seems to have been largely forgotten – the Mulatto Ax

Murders.

One of the connecting threads in these murders, beyond the use of

an ax, was the fact that they always involved blacks, the only

exception being the white wife of a black man in San Antonio, which

did not keep her from being murdered along with her husband and three

children. At least one member of the family was also a mulatto, one

of the reasons Ed Deere was so distressed when he came to visit the

newsroom. He said that

“...his wife was a 'high

yellow”...like himself, and he felt that he was doomed to a

certainty...he remarked that he had always boasted of his color to

his white friends, declaring he was “no nigger,” but was now

sorry he was not as black as tar.”

The relationship of the white press to these murders provides an

often disturbing insight into the distance the white community felt

toward black communities during these early days of Jim Crow, with

the use of the murders to terrorize black individuals and communities

with letters threatening attacks by the Axman. But what becomes

clear from those press accounts is that there was a sense of near

panic in those black communities in Texas that lasted long after the

murders subsided.

The murders began in Louisiana in February of 1910, with the

murder of a mother and her daughter in Lake Charles. In September a

family of three was killed in Rayne, followed in January of 1911 by a

family of three. The next month, a family of four was murdered in

Lafayette, and then the slaughter expanded into Texas when family of

five was murdered in San Antonio, Texas. The following day a family

of four was murdered in Lafayette, Louisiana.

One of the earliest of the ax murders, and the first in Texas,

took place on March 22, 1911. It happened in San Antonio, Texas,

well before it was clear that it was but one of a series of ongoing

murders, but in retrospect it clearly bore many of the hallmarks that

came to characterize the murders that became much more well known a

year later.

Alfred Louis Casaway was born in Louisiana and had come to San

Antonio as a teenager. After forty years of living there he had

become a well known and much respected member of his mixed black and

white community just east of the railroad tracks and train station.

He developed an interest in local politics, finding a job as a

janitor at City Hall and even serving as a bailiff for the grand jury

at one time. For the previous six years he served as the janitor at

the Grant colored school, arriving early every morning to open the

school. He had “

an excellent reputation for honesty and

industry” and “

did not have an enemy. His domestic

affairs...ran smoothly, he and his family living happily together.”

Elizabeth Castelow Casaway, or Lizzie, as she was known to

friends and family, had lived in San Antonio for a few years before

she met her husband. As a younger woman, she had moved to San Marcos

with her widowed father, but she moved out from their home when he

remarried to live with a neighbor. While living there she met a

young cowboy named Sam Lane, marrying him shortly afterward in

February of 1885. Eight months later he asked her to fix her some

“grub,” saying he was going “down country' to find some cattle.

He never returned. There were some reports that although she had a

fair complexion and was generally considered to have been white, “

she

contained a trace of negro blood, on and that account was divorced.”

She eventually moved to San Antonio, where she met Alfred. Their

relationship bloomed, and in 1891 he introduced her to a local

attorney of his to help her obtain a divorce so they could get

married. The lawyer filed for the divorce, which was granted in

1891, but he warned against getting married because of a very serious

problem they would encounter. He was black, and she was white, and

their marriage would violate the laws in effect against

miscegenation.

Since a marriage in San Antonio was not possible, shortly

afterward the couple took a train to C.P. Diaz (now Piedra Negras),

the nearest town in Mexico, and obtained a marriage license and were

married there. But on their return to San Antonio, charges of

miscegenation were filed against them, and Lizzie was summoned before

the grand jury. However, no charges were ever filed against them

after she gave her testimony, and they continued to live together as

man and wife. They eventually had three children together, Josie,

Louise (also listed as Ruby B. in the 1910 census) and Alfred

Carlisle. They lived in a three room house at 517 North Olive

Street, and by all accounts, they were a happy family and got along

well with their neighbors.

On Tuesday morning, March 21, 1911, Alfred Casaway did not show

up to work. Since he had the keys to open the school and the

students couldn't get in, Principal Tarver of the Grant school

called the Campbell household to see why he hadn't showed up.

Richard Campbell was a local attorney whose wife was a sister-in-law

of the Casaways, who lived around the corner from them. Bessie

Drakes lived with the Campbells, and knew the Casaway family as well.

Her child had been playing with their children just the night

before, and she had spent a few minutes visiting with the family on

their front porch when she went to pick her up around 8 o'clock.

Campbell's wife, Delia, sent Bessie over to see why her

brother-in-law hadn't showed up for work that morning, but couldn't

get any response. Delia then went over to the house, but when she

had no better luck, she went around to a window to look through the

curtains. She was horrified to see Alfred laying dead in his bed and

ran home to telephone the sheriff, as well as the constable and

police departments.

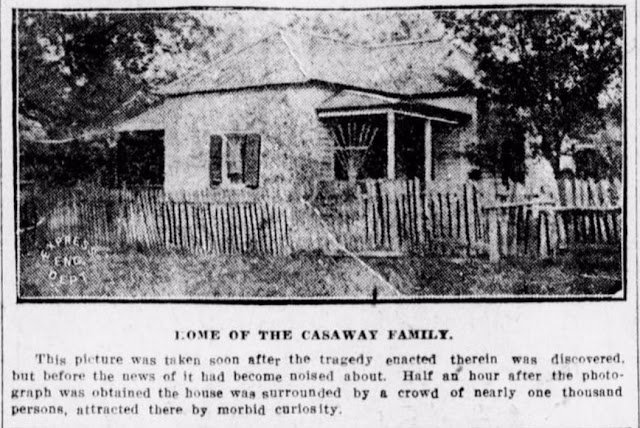

As soon as news of the murder began to spread throughout the

neighborhood, the house on Olive Street became a place of

fascination. A photographer from a local paper arrived early and

captured an image of the house. By the time law officers arrived the

streets were blocked by a crowd of 500 black and white spectators,

which quickly grew to nearly a thousand.

(San Antonio

Express, March 24, 1911, p9)

Bexar County Sheriff John Wallace Tobin was one of the first on

the scene, and from the outset he had a personal interest in the

murders. He not only knew Alfred Casaway from his work as a grand

jury bailiff but Lizzie as well, who had previously worked at his

home as a seamstress. He immediately offered a $250 reward for any

clue leading to the apprehension of the murderer. In the months to

come he would hunt down many leads and at times think he had come to

solve the murder, but it would come back again to haunt him the

following year.

By all accounts, this was the most horrible and brutal murder

that had taken place in San Antonio at the time. All five members of

the household had had their skulls crushed in with the blunt end of a

pole ax, probably taken from the woodshed at the rear of the house

and found at the foot of a bed. Alfred, was found dead in the bed

where his sister-in-law had first seen him, together with his 3 year

old daughter Louise. In a bed in another room were the bodies of

Lizzie, along with 6 year old Josie and the 5 month old Alfred.

Blood splattered the walls, floor and even a child's doll on the

floor, but other than that the house was neat and clean.

The house had not been ransacked, the windows were all closed

and locked, and the rear door was unlocked, with no sign of having

been forced. The rear door was secured only by a thumb latch, and it

was speculated that the family had neglected to lock it before going

to sleep. Almost at once robbery was ruled out as a motive. In

Alfred's trousers, found at the foot of his bed, was a gold watch, a

case with an image of St. Joseph and a purse with some coins in it.

It also held the set of thirteen keys that had not opened the school

that morning, leading to classes being dismissed for the day.

None of the neighbors had heard anything during the night, and the

only possible clue as to the killer were some footprints on the rear

porch which only led a few feet from the house before being washed

away by the previous night's rain.

The lack of good clues did not stop the Sheriff's department from

making arrests. That night a black suspect was arrested, largely

because he was supposed to have made a threat against Casaway at some

point in the past and his shoe sized matched that of the prints found

on the back porch, but he was released the following day. The police

and sheriff's department returned to the scene of the crime,

meticulously examining every article and item of furniture, as well

as the walls and the floors in search of more clues. Again, a large

crowd of hundreds of onlookers of all races, gathered, and boxes and

benches were placed under the windows, allowing the more sanguinely

inclined to look in at the bloody furniture that remained in the

house. The bloody mattresses, sheets and clothing were placed in

the front yard “

preparatory to being burned, although several

negroes protested they should be buried, because they were covered

with human blood.”

(San

Antonio Express, March 23, 1911, p 14)

Arrangements for the burial of the Casaways were handled by

Williamson and St. Clair. Ironically, “St. Clair” was actually

Perry Sinclair, an undertaker who was also the son-in-law of Richard

Campbell, the attorney who was first called by Principal Carver and

whose wife first discovered their bodies.

The funeral ceremonies were held at St. Paul's Methodist Church, and

their bodies were interred at City Cemetery No. 3. The burials were

in three caskets, with Alfred Casaway buried in one, his wife and

their 5 month old son in another, and the girls, Josie and Louise in

a third. The ceremonies were “attended by nearly all the negroes

living near where the Casaways had lived. The murders and the

funeral were the sole topics of conversation, almost, yesterday along

North Olive Street between East Commerce and Nolan Streets and many

of the negroes were wrought up to a high pitch.”

But once the bodies had been laid in their graves and night began

to fall over the neighborhood, the crowds of curious onlookers which

had swarmed around the Casaway house began to fade away.

The house looked lonesome, the

doors closed and windows drawn; everything took on a gloomy aspect

and the shadows about the place assumed curious shapes as distant

lights threw occasional glimmers over all. A dog, the sole surviving

member of the family, sat on the back steps and howled dismally. Few

person passed by, for those who could preferred to go a roundabout

way rather than go by the house in the dark. Those who lived near

appeared to rest badly and frequently faces would be seen at the

windows gazing toward the untenanted home...About 11 o'clock...close

to the hour at which the murders are believed to have been committed,

a little party of negroes was seated in a house near by. The dog,

which had been quiet for some time, suddenly began howling again,

attracting attention to it. As the persons in the group looked that

way a blue light appeared suddenly to leap from the windows of the

house. It vanished, but a moment later again shone forth. Looking

closer, it appeared to the frightened watchers that a light shone

dimly in the house. One of the party was sure heard a sound like a

blow, followed by a sharp cry. The report spread quickly, and soon

many eyes were focused on the house. For thirty minutes the blue

light appeared to shine and then went out altogether. What cause it,

whether a reflection from a distant electric light or what, is not

known. No investigation was made. No one cared to approach the

house. No watch dog was needed to guard it.

As no new strong clues as to the identity of the murderer of the

Casaways or their motives came to light, speculation began to grow.

The dog that continued to wait in vain for its owners on the back

porch was the source of one idea that was to grow over the coming

year about how such a murder could come about. The dog who did not

bark led some police to believe

“...(t)hat had anyone gone to

their house with the intention to commit murder prepearations would

have been made, instead of depending upon finding an ax. One theory

the detectives have had is that the murderer was acquainted with the

family to such an extent that the dog permitted him to pass, for the

animal, if aroused, did not bark, at least not so as to noticed by

any of the neighbors. Persons believe that a dog always knows when a

death occurs in a house and announces the fact by howling

unceasingly, cannot understand how it is that the animal made no

outcry whatever during the night. It has been thought that the dog

may have been doped, too, with something which was used to put the

members into a deep sleep, for it is evident that the murderer went

about his work deliberately, lighted a lamp after fastening cloths

across the windows.”

The suggestion that the Casaways had been drugged had already

been made, but the detectives had decided not to have the contents of

their stomachs examined, feeling that other clues could lead to the

arrest of the murderer.

Another area of speculation involved the mixed race issue, with

Sheriff Tobin “inclined to the belief that the deed was the act of

some fanatic on the problem of miscegenation.”

This was also reported as “

a commonly accepted theory here that

the killing was done by some one who, believing Mrs. Cassaway woman

and being insanely opposed to any mixture of the whites and blacks,

conceived the notion of wiping out the entire family.”

This issue also played a role in the murders over the following

year, where the victims were predominantly mulattoes.

After more than a week with no solution in sight, the murders had

caught the attention of Texas newspapers in Houston, Alpine,

Bastrop, Abilene, Bryan, Temple,Coleman, Brownwood and Galveston, as

well as being reported in national papers in Louisiana, New Mexico,

Oklahoma, Kansas, North Dakota, South Carolina, Utah, California and

Illinois. Confronted with increasing national pressure on a killing

being portrayed as “t

he most remarkable in the criminal annals

of Texas, the murderer leaving absolutely no clue to his or her

identity,”,

the sitting Goverrnor of Texas, Oscar Branch Colquitt, offered a $250

reward for the apprehension of the murderer of the Casaways. Two

days later a mass meeting of the concerned black community was held

in San Antonio as well, with hopes of raising additional funds for

the reward.

When Judge Edward Dwyer of the Thirty-Seventh District court

called together the grand jury a week after the murders, the

importance of solving the crime was made imminently clear in his

charge to the jurors.

Since your organization, I am

sorry to say, a most diabolical crime has been committed in our

midst. The midnight assassin has been at work and exterminated in

one night a whole family – not even sparing innocent and helpless

children. It is a crime that cries to heaven for vengeance and one

that has shocked our fair city and made its citizenship bow their

heads with grief and horror and shame. The officers of the law have

been working day and night to find a clue to this horrible killing,

but so far, I regret to say, have been unable to run down the

criminals, and the outrageous murder is still shrouded in mystery. I

charge you to leave nothing undone toward unraveling, if possible,

this horrible crime, so as to bring the guilty ones to justice. I

also now call upon all good citizens to aid us in every way possible

in ferreting out who has committed this wholesale assassination in

our midst by giving you or the officers any information they may

have, circumstantial or otherwise, that might give a clue toward

detecting the offenders. We all owe it to God, to our State, to

society, to our fair city and ourselves to do all in our power to

bring such miscreants and enemies of mankind to justice and must

unite out energies in that direction...

Immediately after the murders, Sheriff Tobin initiated a search

for Lizzie's family members. Two brothers was located, one in Llano,

and another in Austin. Both were questioned by a deputy sheriff

and a city detective, but neither was able to provide information

pertinent to the investigation.

Several of Lizzie's relatives, including her brother John, her well

to do cattleman brother from Llano, were eventually called before

the grand jury investigating the murders, only to find that a number

thought she had been dead long before the murders.

But it was a more distant family member who had not been interviewed

that was eventually arrested for the murders over four months later

after he had been tricked into showing up at the Sheriff's office.

William McWilliams was a 68 year old white man who had been

raised as a foster child by a relative of Elizabeth Casaway, a Mrs.

Hamilton from Perry Hill, Texas, and was also known as Mack Hamilton.

The Hamilton were a tumultuous family, many of whom who died violent

deaths, and McWilliams eventually lost track track of them after he

moved to the East End of San Antonio. In the spring of 1911 he

received a letter and then a visit from a family member, a Miss

Ballard. It was during that visit that McWilliams learned that

Elizabeth had married a black man and was living less than a quarter

of a mile away from him.

McWilliams didn't believe this at first, and went to go visit

Elizabeth for himself. When he got there he stood outside the gate

talking to her, while watching her children playing in a room of the

house. According to the testimony he gave to law officers, he

initially didn't believe that Elizabeth had married a black man until

he heard her tell him the story of her abuse and abandonment in her

first marriage. He said that Casaway had been kind to her, and that

after they returned from their marriage in Mexico she and Louis were

living a happy life together.

The Sheriff's office had previously been told of his visit with

Elizabeth the day before her murder. She had recounted to another

woman that “

she had been urged to leave her husband and children

and refused to do so.”

This unnamed woman had called in this information anonymously, and

“

refused to give her name, not even, she said, for twice the

amount of the ($250) reward offered.”

They had also received information from a black man named James

Nelson that McWilliams “

talked about having put five negroes out

of the way, that three of them were buried in the same hole. Nelson

further testified that McWilliams had said that Sheriff Tobin was

looking for Mack Hamilton for having done the killing, and wanted

Nelson to understand that he was not Mack Hamilton.”

After he had been arrested,

McWilliams' home was searched and a letter was found whose

handwriting and paper matched those of an anonymous letter which had

been received by the Sheriff's department. That anonymous letter,

received on May 26, had been addressed to Sheriff Tobin and Richard

Campbell, Louis Casaway's brother-in-law, and although at the time

the Sheriff would make a full investigation of it, he also felt it

might well be the work of “some crank.” It intimated not only a

responsibility for the murders as well as animosity toward Sheriff

Tobin, and was clearly the work of a disturbed mind. The full text

of the letter was printed in full in the newspaper two days later.

San

Antonio, Tex., May, 1911. - To Sheriff of Bexar County, and also to

R.A. Campbell, lawyer – I understand that you all are in search for

the man that killed the Louis Casaway family. Well, I am the man,

and I am going to give you trouble in catching me, and whenever you

run across me there will be trouble on your hands.

I am no negro. I am a full-blood white man, and again, I never

wrote this. I had it done by a man that is today about three hundred

miles from here, and I am in the city of San Antonio now. So catch

me if you can and there will be trouble on your hands, because I am

in a dangerous place and I mean to kill the first one that tackles me

about the matter, so you can all pop your whip and get busy. I am

ready to die at any time, so look out.

I

had a right to kill that family, and if you ever catch me I will

explain it to you.

On the basis of this

information, McWilliams was arrested and held in the county jail.

When he appeared at a habeas corpus hearing the following week, most

of the crowd in the courtroom were neighbors of the Casaways.

McWilliams was noted to laugh several times during witness testimony,

and his “aged wife, sitting at his side, also seemed to

find considerable merriment in the proceedings.”

The hearing was not completed that day, and when it continued the

following morning it once again had a large crowd of spectators

attracted by the most spectacular murder in the city's history.

McWilliams' demeanor was noted to be considerably more sober,

punctuated not by laughter but by a severe coughing spell when the

still bloody ax used in the Casaway murder was brought into the

courtroom as evidence.

A federal marshal testified that McWilliams, whom he considered a

nuisance who frequently visited the Marshal's office, had bragged to

him that he knew who had murdered the Casaways, but when he reminded

McWilliams he could receive a $500 reward for that information from

the sheriff's office the reply was “I wouldn't tell Tobin

anything. I have as much use for him as I do for a bedbug, and you

know what to do to a bedbug – kill it.”

After two days of hearings, Judge

Dwyer finally did grant McWilliams bail, set at $1000 per each charge

of murder, but he was unable to make the bond of $5000 and returned

to the county jail to until the grand jury was impaneled in October

to stand trial. But for reasons that remain unclear, McWilliams

never did stand trial for the murders.

Shortly after the Casaway murders the

authorities in Texas were contacted by Louis LaCoste, the Sheriff of

Lafayette Parish in Louisiana. LaCoste had noted a similarity with a

series of murders he had been investigating.

On November 11, 1909 Edna Opelousas, a black woman, and her three

children between the ages of 4 and 9 had been murdered with an axe in

Rayne, a town in Acadia Parish, adjacent to Lafayette Parish. On

January 31, 1911, another Acadia Parish black family, Walter Byers,

his wife and six year son were murdered with an ax in Crowley. On

February 25, yet another black family, Alexandre Andrus, his wife

Mimi, three year old son Joachim and 11 month old daughter Agnes also

fell victim to an ax murderer in Lafayette. When Sheriff LaCoste

heard about the strikingly similar murder of the Casaway family in

San Antonio he suspected the same person may have been involved.

A number of suspects in these Louisiana murders were arrested,

but all were eventually released, save one. On October, 24, 1911

Raymond Barnabet was convicted of the Andrus murders in Lafayette,

but the murders did not come to an end there. The following month,

another brutal murder of a black family occurred in Lafayette. On

the night of November 26-27, Norbert Randall, a 24 year old butler,

his 23 year old wife Asima, 5 year old son Rene, 5 year old son

Robert, year old daughter Agnes and an unnamed nephew were all killed

by ax blows to the head. Their bodies were discovered discovered by

the oldest Randall girl, 9 year old Devine, who had spent the night

at her uncle's house.

The following day Clementine Barnabet was arrested for the murder of

the Randall family, who she was living within a block of. Clementine

was the 18 year old octaroon daughter who, along with her brother,

had testified against her father during his trial the previous month.

Clementine's appearance at a hearing on November 28 was described

as one “t

hat for years will be the subject for 'round-fire'

tales by toothless grandmothers and will form the nucleus for

legendary tales of horror for generations to come...With screams of

hysterical laughter, the girl rocked back and forth in the witness

chair, her great eyes rolling into the back of her head, barely any

of the pupil showing.”

Whether prompted by mental instability, guilt or “

a night in

jail and a third degree”

and a plan by the Lafayette Parish authorities “to be taken to New

Orleans...to have her submit to an examination on the order of the

'third degree' by the New Orleans detective bureau,”

she readily not only confessed to the Randall murders but to the

murder of the Andrus family her father had been convicted of.

Throughout her incarceration and eventual conviction of the murders,

she also claimed be a part of a greater conspiracy, a member of the

“Church of Sacrifice” under the protection of “condjahs”

provided by voodoo doctors to protect them while engaged in blood

sacrifices.

Although the confessed killer was in the Lafayette Parish jail

awaiting trial, the ax murders continued. On January 19, 1912

another murder took place in “

the coontown section of the city”

of Crowley known as the “

Promised Land,” a legally

sanctioned red light district.

Marie Warner was a young mulatto woman who had been divorced from

her husband for four years, but after he left for Beaumont she

returned to their two room home to care for their three children, 9

year old Pearl, 7 year old Garey and five year old Harriet. When

Marie's mother-in-law came to check on her and didn't get an answer

at their front door, she asked a neighbor if she knew where she was.

Finding the back door open and fearing the worst, they found a man

willing to go in to check on them. Although there was no sign of a

struggle, all four were found laying face down on their bed in the

front, along with the bloody ax that had staved in their heads.

Although there were footprints found in the back yard and bloodhounds

were called in, no substantial clue was found leading to the

murderer.

Two days later, on January 21, another black family was murdered,

this time in Lake Charles, Louisiana. Felix Broussard was known as

“a hard working man” who had “an industrious family and bore a

good family.”

He, his wife and their three children, aged 8, 6 and 3, were

murdered with blows to the head from an ax, but this time there were

two additional new twists to the murders. The first was a bucket

found collecting the blood from the blood from the victims beside the

bed. The second was found written on the front door of the family

home, a line of Biblical text which read “When he maketh

inquisition for blood, he forgetteth not the cry of the humble,”

followed by the words “human five.”

With the number of murders growing despite one confessed

murderess being behind bars, the public was in an uproar. In Lake

Charles Eliza Richards was arrested in connection with the murders

despite her adamant claims of innocence. For her own protection she

was brought back to Crowley, not only for “

further investigation

on the part of Sheriff Fontenot and his deputies” but for

safekeeping, “

as the wholesale murders around Crowley have

aroused much excitement and resentment, and probably violence may

have been attempted were any one held there in connection with the

bloody crimes.”

In addition, King Harris and J.W. Wilkins were being held in the

Lafayette Parish jail as preachers in the “Church of Sacrifice,”

alleged by Clementine Barnadet to be the instigators of the murders

as “a result of some fanatical belief or teaching.”

But with the murders now numbering in the dozens, despite the

arrest of one suspect who confessed to the murders and even more

suspects being jailed, panic was beginning to spread through the

black communities in southeastern Louisiana. It was reported that

“

(m)any of the Lake Charles negroes have remained awake since

the night of the murder, while not a few have organized into bands to

watch while the others sleep.”

To make matters worse, there were more attempts “

to enter negro

homes” and “

(v)ery sensational tales are being circulated

in regard to these attempts, which are greatly adding to the fright

of the negroes.”

A book agent asking a black woman in Lake Charles about her family

size and their religion found her so nervous about the ax murders and

suspicious over his line of questioning she became “

began to

shout hysterically and finally collapsed. The scared book agent fled

to a negro cabin which was soon surrounded by a mob of more than a

hundred angry negroes. He was rescued by the police.”

In Lafayette there were a number of attempts to enter black homes

at night, adding to the growing sense of fright among the black

population. This led to a mass meeting of 150 black citizens at the

Good Hope Baptist Church, who having “

been recently visited by

some unknown party, or parties who have committed the most horrible

crimes in killing two colored families in a very mysterious manner,”

adopted a number of resolutions “

pledge(ing) ourselves to

furnish the authorities and officers with any information we may have

that would lead to the fereting out of these crimes and we further

pledge ourselves to be used in any capacity by the authorities and

officers of our city in helping them bring about the desired results

in reference to the crimes committed in Lafayette, Rayne, Crowley and

Lake Charles.”

And the panic was soon to spread westward into Texas.

On the night of February 18-19, 1912, the ax murderer crossed

over from Sabine River from Louisiana into Beaumont, Texas. 39 year

old Hattie Dove, a divorced black woman who worked as a domestic, was

last seen at home that Sunday night with her three children, 18 year

old Jessie Quirk (divorced), 16 year old Ethel and 14 year old

Earnest, who worked as a laborer. Another extremely fortunate man

who boarded with the Dove family worked nights, and was not home that

evening when the now infamous “ax man” slipped into their house

on the north end of town, wiping out yet another family. It was

reported that

“Thousands

upon thousands of negroes filed past the four dead negroes lying in

the morgue...(a)nd sent fervent supplications to heaven to be spared

a visitation of this awful vengeance upon themselves. Many of them

moaned that the Lord had deserted them and some of them were heard to

murmur that a curse had fallen upon the race.”

As usual, the police rounded up a number of suspects and detained them but eventually they were released. There was a mass meeting of concerned black citizens and they raised a reward of $500 for the arrest and conviction of the murderer. Tensions were running high and members of the black community were spending nights together, staying up in shifts to keep a watch out for any sign the ax murderer might decide to grant them a visit. Horace Alexander, a 21 year old married man was sharing these duties at the home of Adam Bobinaux on the south side of Beaumont on the evening following the Dove murders. Bobinaux was sitting up with the shotgun when he somehow mistook Alexander for the “ax man,” shooting him in the side and killing him instantly.

45 In nearby Orange, there were “more revolvers purchased ...by negroes than was ever known before.”

46

Reports about the murders and Clementine Barnabet's sensational confessions were becoming more widespread in newspapers not only in Louisiana and now Texas, but throughout the country as well. The managing editor of the Utica Saturday Globe, A.M. Dickinson had traveled from New York to Louisiana and penned an extensive article on the Louisiana murders for the February 17, 1912 edition of his paper. It dealt with the murders in Crowley, Rayne, Lafayette and Lake Charles at length, and was complete with photographs of the houses where the murders took place, a “church of the 'Blood Atonement'” and members of the church being held in the Lafayette jail. It was captioned “Like the Jungles of America – Blood Sacrifices in the Louisiana Rice Belt.”

47

Another particularly lurid article on the murders appeared in the El Paso Herald, titled “Voodoo's Horrors Break Out Again.” The tone of the article is captured by it's subtitle, “How the Cruel and Gruesome Murders of Africa's Wicked Serpent Worship Have Ben Revived in Louisiana by a Fanatic 'Sect of Sacrifice.'” It was dominated by an illustration of a small black child wrapped in the coils of a massive snake, describing how “Here all the horrors of Voodooism are revived and little children go to their deaths a sacrifice to the serpent,” next to a photograph of “A Typical Group of Louisiana Rice Pickers from Whom the Victims of the “Sect of Sacrifice” are Taken” and above a picture of “How the Dead Fingers of the Baby Victims Are Spread Apart with Pieces of Wood After They Are Sacrificed!”

48

(El

Paso Herald, March 14, 1912, p13)

The fear was spreading, and the mysterious murderer or murderers had a name - the Axman. On March 1, a story began circulating in Galveston that the Axman “had posted notices that his toll in Galveston would be 'twenty-three negroes,' and as a result the panic was wild. It was made necessary to call in an extra policeman from the reserve list...to stay at the station and answer telephone calls as well as assure frightened dusky callers that they would receive protection.”

49 The press, feeling somewhat bemused and perhaps slightly insulated from a series of murders that only struck the black population, ran a skeptical article on the varieties of responses the black community of Chenevert in Houston was responding to this fear.

Darkies are Panicky.

Report That Mysterious Axeman Is

in Houston Causes Those of Chenevert District Sleepless Nights.

Midnight oil, mysterious pans of

cold water, uncanny exorcisms, knotted horse tails and too many other

forms of incantations known to darky necromancy are playing part in a

panicky epidemic through the Chevert neighborhood.

This sudden oscillatory, seismic

disturbance in the peace of mind of the colored population of

Chenevert street had its origins in a rumor, from some source that

has not been run to its lair, that the author of the recent negro

family massacres around Beaumont and Lake Charles had come to Houston

and is now stalking the night in the Chenevert neighborhood.

In hope of keeping this mysterious

and sinister being, man or devil, or whatever he or it is, away from

their houses, the whole population is reported to have resorted to

methods of the description alluded to above. Oil torches are left

burning in their rooms all night, pans of water are placed on the

floor and elsewhere about the room for the purpose of absorbing any

portion of the evil influence that may happen to be hydrophobic, and

other prestidigitations are performed carefully and thoroughly before

retiring, in hope that those thus doing may be immune when the

monster passes.

In order to supply the increased

demand of oil growing out of the large consumption for this purpose,

some of the Chenevert grocery and supply dealers on Chenevert street

found it necessary yesterday to lay in extra quantities of kerosene,

while the pan demand took on the proportions of a small flurry.

The

Chenevert negroes have applied the name “Jack the Ripper” to the

otherwise unidentified axman whose alleged presence in their midst is

spreading terror. That some sinister joker is perpetrating one of

the superstitious darkies of that side of town seems evident.

But the next murder was to bypass Houston for a small town next to the railway tracks outside of Columbus, Texas by the name of Glidden. It was discovered by Parthenia Monroe, the 30 year old who lived with her grandmother when she came to check on her mother, 46 year old Ellen Monroe, a local washwoman and mother of 8 children.

51 When Parthenia came by early on the morning of March 27 to check on her mother and younger siblings, she found they had been brutally murdered in their beds. In one room were 8 year old Alberta, 11 year old Jessie (also known as Octavia), 12 year old Dewey were in one bed and 16 year old Willie on a cot, their heads crushed with the blunt end of an ax. In the room across the hall, lying dead by the side of the bed, was Lyle Finucane a widowed 35 year old mulatto

52 who worked as a porter in the rail yards and who roomed with the Monroes, his head also “crushed in and beaten away from the crown to the nose.”

53 Ellen had apparently risen after being struck but only made it to the middle of the room before she died from her wounds. The ax, which had been taken from a woodpile out back, had been left in the house, and the murderer had stopped to wash his hands in pan of water before he left.

(The

Glidden Murder House, from Around Columbus by Roger C. and Marilyn

B. Wade; courtesy Nesbitt Memorial Library)

The following day five wagons carried the six coffins to be buried at Rocky Chapel, and nine blacks were held “under arrest, believed to have knowledge of the crime,” though the Justice of the Peace Gregory waited “until after the burial of the victims before taking further testimony.” Only one of these, Jim Fields, eventually went to trial for the murders, while most of the others were held as material witnesses, including his wife, Ida Fields. . Meanwhile, the Mayor, Sheriff, Chief of Police and City Detective of Beaumont came to Columbus to determine if “the perpetrator of the outrage has any connection with the crime of similar character lately committed in Beaumont” but were “of the opinion there is no connection between this crime and series east of here.”

54

But at least one unnamed attorney from Lake Charles felt that there was some sort of connection between these murders, and had mailed a letter to Constable J.M. Everett of Columbus “foretelling of the tragedy at Glidden and predicting that after it the perpetrators would proceed to San Antonio, where another family had been marked for slaughter.”

55 It was similar to an letter that had been received by the San Antonio City Marshal, dated April 2 and stating that “a crime identical with that of the Caraway(sic) atrocity would be committed in San Antonio on April 12.”

56

Early on the morning of April 12, 1912, Callie Burse, a young

black maid, was sent over to the house of William Burton at 724

North Center Street in San Antonio just east of the railroad station.

She a can of kerosene sent by a local preacher to repay a loan of

the same by Burton, a 26 year old porter who worked at Sommer's

Garden, a local saloon and bowling alley. No one answered at the

front door when she knocked, so she went around to a side window. To

her dismay, the curtains on the window were down and covered in

blood. She “

made no further investigation, but notified

neighbors, who called county and city officials.”

When the police forced their way into the house they came across

the body of Burton's 20 year old wife, Carrie, face down on the floor

next to the bed, her skull crushed in and a knife sticking out from

her back. On the bed was Burton, his head also crushed in and a

knife in his back as well. In an adjoining room the Burton's two

children, 3 year old Naomi and 1 year old Edward, were found with

their skulls crushed. Carrie's brother, Leon Evers, who had been

staying with the Burtons, was dead on the bed next to the boy, skull

fractured from an ax blow and a knife blade broken off in his back. A

bucket of water was found in the room, where the killer had washed up

after the murders.

The Burtons had lived a few blocks away from where the Casaways

had been murdered less than a year earlier. As with the Casaways,

aside from the slaughtered bodies of the victims, nothing was out of

order, ruling out robbery, and all the doors and windows locked.

Cassie Burton's mother, Betty Evers, had been by to visit the home

around 8 the previous evening, and William Burton returned home from

work around midnight. Neighbors said he had no enemies, but a next

door neighbor said she had heard some odd noises at the Burton house

around 2 in that morning when her dog began to respond to those

noises, though she thought nothing of them at the time.

(Burton

Home, San Antonio Express, April 13, 1912, p 14)

It became clear that the dreaded killer known as the Axman had

returned to San Antonio. The police and the Sheriff's department

that “

the crime was the result of religious fanaticism. This

belief is based upon the similarity of the condition in which the

bodies of the victims were left in this tragedy and other mysterious

murders which have occurred in South Texas and Louisiana.”

Constable J.M.Everett came to San Antonio, along with the letters he

had received, to see if he could further his investigation of the

murders in Glidden. Three men were arrested in connection with the

murders, including two “'voodoo' doctors” from Alabama, but both

denied “

any knowledge of the horrible butchery which has thrown

seventeen separate and distinct kinds of scare into every negro in

the city.”

Sheriff Tobin began to work under the assumption that “

these

murders are part of the religious propaganda of a secret sect”

and that the fact that Cassie Burton, her brother and two children

were mulattoes played a role in their murder.

He

...requested that all negroes who

know anything of the practices of 'voodooism' confer with the peace

officers. Their confidence will be respected and they will be

afforded police protection...From one old negro yesterday he learned

that the “human sacrifice” idea is taken from the Bible, St.

Matthew, iv. 10, as follows:

'And now also the ax is laid unto

the rot of the trees; therefore every tree which bringeth not forth

good fruit is hewn down and cast into the fire.'

Under a diseased condition of mind

this is believed to have been warped into a literal command from the

Most High to commit murder under certain conditions. Possibly the

fact that the Burton woman was fair-skinned may have been the

incentive in this instance. So far as known, however, she herself

was not imbued with fanatical religious ideas, but lived a quiet and

respectable life with her husband...

For the second time in less than a year, blacks in San Antonio

began to fear that their family might become the next victims of a

horrendous midnight slaughter, especially if there was any white

blood in their background. One of the suspects, arrested after the

murders with a large amount of skeleton keys, had been called upon to

treat corns on a black woman's foot, and when another woman in the

house, a mulatto, asked for him to treat her he “

said he would

not treat a woman of her color...for a million dollars...and that

there would be an end to negroes of her hue.”

In many houses one family member stood guard half the night,

while another stood watch the other half of the night. Some nailed

their windows shut, keeping the curtains up and the lights burning

throughout the night so neighbors could help keep a lookout, and dogs

were now allowed in the house to help raise an alarm over any

intruders. “

In some quarters there was an intensity of fear due

to letters sent from Houston.” These were turned over to the

police, unsigned chain letters which contained the prayer “

We

implore thee to bless all mankind and keep us from all evil and take

us to dwell with thee,” and instructing the recipient to “

copy

it nine times and sen(d) it to nine friends with the promise that

'you will receive a great joy on the ninth day.' In conclusion, it

says, 'Do not break this chain – sign no name, just date.'”

A number of blacks in San Antonio “

appealed to the Sheriff

and police departments for permits to carry weapons, and others,

without such permits, have resorted to the use of firearms when

aroused by strange noises at the dead of night. Two such cases were

considered in police court yesterday and it is reported that several

similar arrests have occurred in which no arrests were made. “

The chief of police called upon “

the city council to offer a

$1000 reward for the capture of the fiends who slaughtered the

Burtons, and Sheriff Tobin will make a like appeal to the governor.”

William and Cassie Burton, as well as their two small children,

were buried in City Cemetery #3, San Antonio's colored cemetery, the

same as where the bodies of Louise Casaway, Lizzie Casaway and their

three small children had been buried less than a year before. But

before the funeral services for the Burtons could be held, the now

infamous Axman was to claim his next victims.

Isaac Burney had been born into slavery in Georgia in 1855, but

had made his way to Texas by the age of 20, when he married Sylvia

Johnson and had six children before she died some time before 1900.

He was a preacher as well as a farm laborer, and in 1912 he was

living a block east of the court house in Hempstead, together with

his daughters, 20 year old Cassie and 30 year old Alice Marshall,

along with Eva Jones and her two small boys.

The night following the murder of the Burton family, As he slept

he was battered into insensibility by blows from either a small ax or

a hatchet, although he did not die immediately, lingering on for

three days before succumbing to his wounds. The assailant then crept

into an adjoining room, where his two daughters and Eva Jones slept.

Alice was killed immediately, her head similarly crushed in. Cassie

was also struck, but before any fatal injuries were sustained Eva

awoke and managed to escape with only slight wounds to a hand before

rolling under a bed and scaring off the murderer with her screams.

This not only saved her life but probably those of her two sons and

Cassie as well.

This was the most atypical of the killings attributed to the

murderer, primarily because the killing was interrupted before every

in the house was killed, but also because none of those killed were

mulattoes.

But it is also unique because the killer had become so well

established in the public's consciousness by this time that on Alice

Marshall's death certificate the cause of death is simply listed as

“Killed by the Axeman,” although the signing physician was

slightly more circumspect three days later when the cause for Ike

Burney's death was given as “Struck on head by the Axman or some

unknown party.”

Alice Marshall's Death Certificate's Cause of Death

Sheriff Tobin, strongly suspecting links between the murders,

sent off detailed copies of the Burton murders to law officers in

Glidden, Hempstead, Beaumont and Lake Charles, with requests for

information on the murders in those communities, noting similarities

such as the presence of at least one mulatto and children in the

cases. Reporters also noted that

Since the five bodies were found

at the Burton home men in the Sheriff's department have been busy

running down every available clue and the affair at Hempstead,

seemingly similar to the one here, has redoubled their efforts. In

an effort to determine whether all of these mysterious murders which

have taken place at dead of night in various towns in South Texas and

Louisiana are not directed by intelligence, Sheriff Tobin dictated to

his stenographer yesterday a full and complete account of the one

here. Copies of this were sent to Glidden, Hempstead, Beaumont and

Lake Charles, La., with a request that the peace officers in those

communities perform a like service for him. The information now at

hand indicates that all of these crimes were similar, the

distinguishing features being the families attacked contained at

least one mulatto, that there were children in all cases, and in each

instance some sharp instrument, such as a knife, was left sticking in

the back of the victim.

It is the belief of those who have

been working on the case here that the murders are due to the

fanatical psuedo-religious teachings of a mysterious Church of the

Sacrifice, whose ritual is reputed to be a queer jumble of voodooism

and biblical quotations. This organization also has many of the

characteristics of a secret society and, if reports which have

filtered in to the police are true, those who are initiated into the

mysteries guard them with zealous dread.

An old negro woman who conferred

yesterday with Sheriff Tobin intimated that she knew something of the

cult. She was wrinkled, decrepit and wore an old bandanna

handkerchief about her head. Just who she was the sheriff declined

to say, nor did he place much credence in her story. She explained

that the words “blood of the lamb,” used figuratively by

Christians, has a more literal meaning in voodooism, and gave this as

a reason why children are killed.

The fact that the object of these

murderous attacks are mulattoes is firmly established in the minds of

the negroes and, while all members of that race here are more or less

apprehensive, in those families where one or more is light-colored

the fear is openly manifested. From midnight until dawn the mounted

police are kept busy answering calls...

By this time the Axman panic was firmly entrenched in the minds

of blacks throughout Texas and becoming a common item in newspapers.

In Austin, the older blacks recalled the unsolved “Servant Girl

Murders” of 1884 and 1885, when five black women and one black man,

as well as two white women were murdered and “

voodoo doctors”

were suspected of “

waging a causeless war of extermination”.

A black tramp who had recently arrived and was asking for food was

feared to be an Axman. Similar suspicions about another stranger who

had been hired to work on a black work gang led the crew to refuse to

work until he was fired. When unsigned letters purporting to be from

the Axmen were found in several East Austin front yards a delegation

of black citizens met with the Sheriff and asked for extra patrols in

their neighborhoods. The sheriff requested all copies of any

letters, but the only one received was eventually “trailed to its

source and found to be a joke. A group of black leaders presented a

petition to the governor requesting that he authorize a reward for

capture of the Axmen.

The colored population

secured all the guns they could find. Much excitement prevailed all

night and many windows and doors were nailed up.”

In Bryan, fear that the Axman was in the black section of town

caused “

a big excitement...(t)he whole population was soon up,

with lights burning and preparations made for defense. A search of

the neighborhood failed to reveal his presence and quiet was

restored.” In Hearne the presence of a chalked letter “s”

over the doors of homes in some areas, led many to fear the Axman was

marking the homes of his next victims. This was coupled with an

unexplained failure of electric lights in the town, but although law

officers were on heightened alert, “

(n)o clue has yet been

found, nor have they found anyone who saw the houses being so

marked.”

Similar “Black Hand” letters were received by some prominent

black ciitizens in Georgetown, followed by warnings from someone

presenting themselves as an Axman. “

Although Jim Fields was still being held for the murders in

Glidden, with his wife offering to give testimony against him, on

April 17 “...

a mass meeting of white citizens was held at the

courthouse to placate the negroes, to give them moral support and to

offer any feasible protection that lies within their power against

the axman...The object of the meeting was stated by the chairman to

be sympathy and protection of the colored people against the axman.”

The meeting, whose audience was about a third white and two thirds

black, was addressed for almost two hours by many prominent white

citizens, including the sheriff, county judge, justice of the peace

and others, as well as S.H. Burford, a black physician. A pharmacist

at the meeting, however, “

warned the negroes of the sanitary

effect of close crowding and sleeping with closed windows and doors.”

The chairman of the meeting stated it's object was “sympathy and

protection of the colored people against the axman,” and adopted a

resolution “

requesting the Governor to offer a suitable reward

for the apprehensions, capture and conviction of the axman.”

The depth of the fears of the black populace and the horrendous

character of the murders finally caught the attention of the governor

of Texas, Oscar Branch Colquitt. But it was the growing number of

letters supposedly from the Axman that brought him to act on this

growing menace to citizen of his state. On the afternoon of April

19, he “

issued a proclamation reciting that his attention had

been called by numerous persons in various communities that negroes

were receiving threatening letters in which the writers threatened

assassination by the “Axeman.” He therefore offers a reward of

$250 for the arrest and conviction of any such person found guilty of

writing or sending such communications.”

This did not stop such letters from preying on the fears of

blacks for many months to come. In Victoria, “quite a number” of

blacks were victimized by letters “

typewritten on slips of bill

heads,” supposedly signed 'The Axman' and 'The Hatchetman.'

They were “

thought to be no more than the work of some joker.

One read: 'We warn you, you half white, and all your family to leave

town in ten days.''

In the coastal town of Rockport the receipt of several “

Voodoo

letters” led the black community to form “

an organization

to protect themselves against expected visits of the 'axman,'”

including a committee to “

visit each incoming train to note the

arrival of strange negroes” and one to “

try to secure

permissions from the police officials to carry weapons.”

In Luling slips of paper signed “

Ax Man, Majority and Gamge,

no. 25” were found under the doors of black residents warning

them to “

either vacate their buildings or leave the town

permanently,” causing some to move out immediately.

Letters from Houston were sent to four blacks in Columbus “

with

pictures of skull and crossbones, a head with an ax sticking in it

and other devices with the words; 'June 19.'”

A family in Houston received a particularly ornate and

threatening letter. “

The envelope had been edged in black,

making it a good imitation of mourning stationery, and in the center

was a black coffin. Stamped on each corner with a rubber letter

printing outfit was the following inscription: “blood We Want and

Blood We Must have.” The letter inside read “

The axman is

in town and he is not a negro. This is a warning for you. Blood,

blood, blood.” This threw the entire neighborhood into a

panic, and when the police arrived to investigate the letter they

gave up on trying to “

persuade the negroes to return to bed and

the officers left them talking of the letter and hovering in groups

supposed to meet any attack from the 'fiend.'” An

investigation by detectives felt “

that the letter is the work of

some school children playing a joke at the expense of the

superstitious negroes.”

Another family received a less ornate letter. “

A large

crossbones and skull were drawn crudely in the center and a large ax

underneath. 'Look out, I am coming; you are next' were the words

written on the paper, and it was signed 'Ax Man.' It is the opinion

of the police the this letter is the prank of some friend taking advantage of the woman's fear of the 'fiend.'”

The Houston Post reported a story of a cruel joke played with a

potato. A porter on the return train from Beaumont went into the

depot master's office to change from his uniform into his street

clothes, but came running out so quickly he had to be stopped by

several depot officials and a police officer. The cause of his

fright was a potato on his suitcase carved to “

resemble a

message from the 'ax man.' It had a skull and cross-bones, the

porter's initials and the sinister legend, 'You next' engraved

thereon. It was signed 'the ax man,' too.” This apparently

caused so much amusement that someone took the potato and changed the

initials to those of a hack driver and dropped it in his carriage,

who reportedly was so frightened he changed from working the day

shift to the night to avoid the Axman's attentions.

In Elgin, “

(t)he axman fright had about subsided here when a

negro man received a card

reading thus: “Harry, you are next from Axman. Mean Axman.”

The negroes are again in a perfect state of agony and despair.”

The

use of threatening letters was still being used in September as well,

with one being turned over the Sheriff in San Marcos being clearly

meant to terrorize blacks. It read

Sarah Adams,

San Marcos: I want to warn you that San Marcos is our next place and

we are after all these stray niggers like yourself. If you are there

when we make our raid we are mighty likely to get you. These stray

niggers running over the country are the ones we are after. It will

only be a few days before we get there. You can take notice if you

don't think we mean business. Wait and see. Your are not the only

ones we are after in San Marcos. You had better lite out before we

get there, which will only be a few days. We always send a letter

ahead, in that way they don't believe it. AX COMMITTEE.”

These attempts to frighten blacks were not limited to letters.

The appearance of a “

peculiar looking man” in Plano who

“

visited many places in the negro quarters of the town, trying

gates and prying around” aroused “

a panic among the local

negroes, some of whom armed

themselves and called on the officers for protection,

which, of course, they were assured they should have.” The

next day

“...about a dozen

signs were found posted about the abodes of the colored population,

and while they bore different wording, all were to the effect that

the “ax-man” was coming, and the negroes had only 24 hours to

make their get-a-way. This work is generally believed to have been

done by boys who, knowing the superstitious nature of the negro,

sought to frighten them. The better classes, who work

and try to do right, have been assured that they shall not be hurt,

and most of them went back to work Tuesday morning, although some of

them were reluctant to do so. Of course the entire matter is

regarded by the whites as a joke, and no trouble is anticipated by

them.”

A letter to the

Alto Herald also addressed the cruelty of these letters.

During the last twelve months a

large number of negroes have been brutally murdered by some person or

persons in Texas and Louisiana. In every instance, men, women and

innocent little children have been brained as they asleep in their

homes. The indications all point to the murderer being a negro, for

an ax is the favorite weapon of the African. No matter whether he be

black or white, I hope he will soon be apprehended, and will meet

with the fate he so richly deserves. Following these brutal murders,

many negroes are receiving anonymous threatening letters, evidently

written by some hellish white man, which have caused much unnecessary

uneasiness among the blacks. Such an act is the height of brutality,

and the writers lay themselves liable to a sever punishment if

detected. They ought to be hung. --- Harpoon

Elijah Branch wrote in a letter to the Houston Post giving his

views as a black man, suggesting that the post office should begin

investigating these “blackmail letters” for possible clues to the

Axman's identity.

All efforts should be made to run

down the 'ax man' – the right one. It is possible in some cases

for an ignorant negro to be caught, one who has not enough

intelligence to exonerate himself, and yet he may be innocent of the

crime.

It ought to be determined by the

officers of the law, first, whether this killing is inspired by a

well organized society whose sole purpose is to intimidate the negro

race or whether each case is independent of the other. In many cases

persons have received blackmail letters which should become the

property of the postoffice inspector, so he could examine same and

see where mailed and what connection they bear to one another, if

any. This, in my judgment, would be the only starting point for the

postoffice department.

I can only speak for my people.

All of the law abiding negroes will unite with the peace officers in

helping to run down these criminals, regardless as to who they are,

and from the fact that they never have and never will be 'desirable

citizens'...

In Lafayette, Sheriff Lacoste even received an Axman letter in

May. It's author, “

evidently a negro,” claimed to be a

member of “

the '105,' who are banded together to kill negroes”

and “

that he is disgusted with the ax murders and willing

confess his part in them...The letter makes the interesting statement

that the victims of the axman are marked in advance by a man who goes

into the towns and makes the necessary selections of victims, who are

then dispatched by others. The writer deprecated the murders, but as

his authority for them, cites the sixth and seventh book of Moses.”

The sender of the letter also stated he was not afraid of being

caught by law enforcement officials, but “

is certain to have

death meted out to him by his fellows.”

Although some blacks were using unique techniques for protecting

themselves, such as the man in Columbus who “

has a system of

fishing lines connected up to a cowbell that looks like a monster

spider web,” most were taking to sleeping together, often at

times with “

as many as fifteen in a small house with windows and

doors battened. Others divide watches and stand guard.”

Having death meted out by one's fellows was a definite hazard for

during the Axman panic, as Adam Bobinaux had found out in Beaumont

when he accidentally shot and killed his friend Horace Alexander.

“

All over Texas and Louisiana the colored people” were

“...sleeping behind barred doors...with shot guns and pistols

inready reach of the watcher, who is prepared to shoot on slight

suspicion.”

In Houston it was “

not regarded as safe for a negro to move

about after dark among people of his own race, as many of them

announce an intention to shoot first and ask pedestrians as to their

mission afterward.”

Law enforcement officials in San Antonio were requested by several

black citizens to be issued “

permits to carry weapons, and

others, without such permits, have resorted to the use of firearms

when aroused by strange noises at the dead of night,”

with several arrests being made for related firearms offenses. It

was reported that in Hallettsville the amount of ammunition being

sold to blacks was greater than it had been in previous years.

In Brenham, the firing of guns and pistols by blacks who had “

been

arming themselves for defense against the terrible butcher who slays

people while they sleep” that the city marshal “

determined

to put a stop to the shooting and a number of arrests will probably

be made as the result of the shooting and of the frequent stealing of

cartridges from Brenham stores.”

The constable in Gonzales arrested two blacks tenants for shooting

at someone sneaking through some underbrush, fearing it was the Axman

when it was just the landlady attempting to locate a turkey nest.

(Dave

McKinney of La Grange. Photograph was taken by local whites mocking

the Axman scare, and is courtesy of the Fayette Public Library and Archives)

Dan Green, of Yoakum was demonstrating to his wife how to use

their shotgun “i

n case the axman made his appearance while he

was absent” when it accidentally discharged both barrels and

shot their daughter in her arms and thighs.

A unnamed white man was traced from a trail of blood after he

attempted to break into the Elgin home of “

a negress, Mary

Colter” and found himself on the business end of a shotgun

wielded by her teenage son, who feared he was the Axman.

Willie Harris woke from a dream of the Axman and ran out of his

house in terror, crashing through a glass door and cutting his arms,

legs and body. Other occupants of his rooming house awoke and

followed him as he ran down the street, leaving “

a trail of

blood on the sidewalk as he ran and ...not overtaken until he fell

exhausted nearly a mile from the house.” Doctors feared he

might not recover from his wounds.

A Houston Post reporter speaking

to a local black man got details of a local “vigilance

committee which was formed for the purpose of protecting the entire

neighborhood.” The men on

watch were required to make five rounds of his neighborhood during

his nine hour watch, and was fined five dollars if he was found

asleep while on duty. The interviewed man stated that while sitting

on his porch on watch one night saw someone on walking around a house

carrying what he was sure was an ax. He picked up his shotgun, went

to the gate of the house and ordered the figure to stop, which it

did. Despite his fright, the man on watch warily approached with his

shotgun at the ready, only to find that what he had thought was an ax

was a shovel being carried by the man who owned the house, who had

been walking in his sleep.

This fatal combination of fear and firearms lead to two deaths in

Smithville on April 16. Ernest Smothers, unable to sleep, got up and

was walking around in his room in a house where Wes Duval was on

guard against the Axman. Duval, “

nerves tautened by the long

watches of a week...ran into the room, and without looking about him

shot the supposed intruder, killing him instantly.” The sound

of the shotgun raised an alarm in his neighbor, Max Warren, who

grabbed his gun and ran over to render aid. But when he got there,

he lost his nerve and headed back to his own house. Yet another

neighbor, Morris Sellers, had also heard the gunshots and when he

saw Warren running mistook him for a fleeing Axman and shot him.

Both Duval and Sellers were held on homicide charges for a week

before being released on $500 bail.

Despite the deaths in Smithville, the Houston Post reported on

“

(t) first real ax man scare in which was blood was shed

occurred yesterday morning” on the 19

th of April.

The Brehnam Daily Banner, playing on the Houston report, went so far

as to report that “

(o)ne of the dreaded axemen has been caught

at last, much to the gratification of many terrorized negroes who are

in mortal fear of having their heads split open at night by the demon

with an axe.” These stories were based on the arrest of

Crawford Bray, a 42 year old junkyard worker who had been arrested

the previous morning after he had terrorized a Houston neighborhood.

After drinking way too much whiskey, Bray returned at three in the

morning to the home of Prince Judge, with whom he'd had supper the

previous evening. When Judge hesitated to let him in, Bray responded

“

I am the ax man; I want to get in the house, and if you don't

open the door I will blow up the place with with dynamite.”

Bray did indeed have an ax, which undoubtedly made Judge less

inclined to let him in. Bray broke a window, crawled in through it

and attacked Judge with the ax, slashing his arm. By this time the

house was in a general uproar, with the women of the house screaming

and the men rushing down to confront Bray, who began swinging his ax

at them. By this time the entire neighborhood was awake and in an

uproar over the possibility of the Axman being about, and an armed

posse led by a local preacher, Rev. E.B. Evans, on the way. Bray

attempted to escape by the back door but was captured before he could

leave, and led by “

a special committee of seven, five of whom

had shotguns...appointed to conduct him to police headquarters.”

Along the way, Bray began to sober up, and on arrival is reported

to have told the Chief of Detectives “

Boss, I sure is sorry

about this thing, and I wouldn't have had it happen for $5000. I

never is been in trouble and I never wants to be again.” He

was held for assault to murder, although the charges were dropped 11

months later. Rev. Evans used the episode to relay to the police

that there was talk in the black community of forming a “

law and

good order committee” offering a reward for anyone posing as an

Axmen and “

that the negroes were in great fear of the ax man

and were honestly afraid and not putting on.” There were also

reports that the neighborhood had received “

several sheets of

paper with skull and cross bones with an axe crudely drawn,

containing the words, 'I am the axe-man – coming soon – you are

next.'” The police, in turn, issued orders “

to arrest

suspicious characters, black and white and all persons who fail to

give a good account of themselves.”

Although the Axman was taking no white victims, his presence was

nonetheless being noted in the white communities throughout Texas. A

Temple newspaper article noted that the Axman scare had struck

locally, and “...

(i)f you haven't seen or heard of him, most

assuredly you have no communication with the colored population. The

axeman is the most dreaded boy that has come to disturb the peaceful

dreams of Senegambia since the long ago days when the “Paterole”

or the “Ku Klux” rode the lanes and by-ways.” Although the

article, titled

Axman'll Get You If You Don't Watch Out, was

clearly made for white readers who might find the whole matter

somewhat amusing, it did note that “

it

is to be considered that if a like epidemic of killing of families

were to prevail with white folks as victims, there would be just as

much fright as there is now, among the darkies.”

The Seagull Yearbook of Port Arthur High School, 1912, p73

The all night vigils

watching for the Axman were beginning to take a toll on whites

dependent upon black workers as well. As far away as Louisiana it

was being noted that the “axeman's

crimes have negroes of south Texas in a state of terror at this time

and in many instances they have stopped work, making the labor

problem a serious one.”

It was reported that around Columbus that “domestic

services in the town and field work in the country is seriously

interfered with. It is almost a daily occurrence for a cook or a

yard man to report that they can not stay awake all night and work

all day and that they will quit their positions to stay awake all

night and sleep all day.”

A local eatery in Bryan even attempted to capitalize on this with

ads such as “When

cookie is scared of the axeman and don't put in an appearance or wife

feels indisposed, call on the Owl Dairy Lunch”

and “Say, did you find

an 's' on your door this morning? Well, don't be afraid of the

axeman, for that is the first letter in 'stop at the Dairy Lunch.'”

A fascination with the possibility of

voodoo and it's racial undertones, compounded by the sensational

confessions of Clementine Barnabet, fed much of the fascination that

reporters were finding in the Axman story. An example of this can be

found in this article, which mistakenly refers to Barnabet's last

name as Crawford.

Despite

the Crawford woman's denials the peace officers are convinced that

she was but the instrument of a more powerful intelligence and her

arrest has involved a “witch doctor,' who confesses to having

provided her with certain “charms.” If the theory of the police

here and elsewhere is correct these charms play an important part in

the religious observances of the Church of the Sacrifice, and if the

head of this sect can be located it is probable he will be subjected

to surveillance, if not arrest.

These crimes have stirred up the